35.3 Glade Walkthroughs

35.3.1 Building the GUI

We will use a simple application to illustrate glade in action. Our sample GUI will be for a tool to count the number of lines, words and bytes in a file—nothing complex but suitable for demonstration.

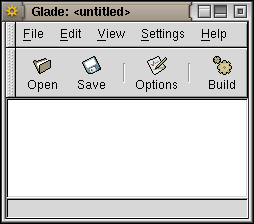

35.3.1.1 The Glade Windows

Start glade from the

Programs\(\rightarrow\){Development} menu of the

GNOME desktop (or else use Ctl+F2 and then type in

glade to start the application). You will see three new

windows popup. These constitute the glade interface.

{#fig:glade-startup}

{#fig:glade-startup}

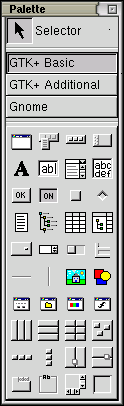

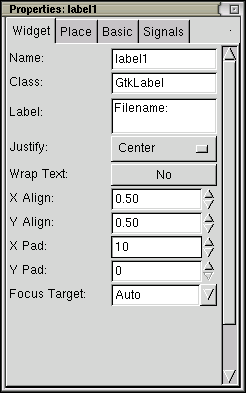

The left most window above is the main glade window which will list the windows and dialogs of your own project. Currently it is empty. The middle window is the Palette window from where you choose the user interface widgets to include in your interface. The right window is the Properties window where you can edit the properties of each widget such as its size, behaviour, and signals it responds to. There are two other glade windows not shown but which can be displayed by selecting them from the main window’s View\(\rightarrow\){Show Widget Tree} and View\(\rightarrow\){Show Clipboard} menus. We will see them later.

35.3.1.2 Project Options

Our first task is to start a project by editing the Project Options through the Options button of the main glade

window (or else through the File\(\rightarrow\)Project Options menu). By default the

Project Directory listed is set to

/home/guest/Projects/project1 (where guest is the

current username—it will be your username in your case). In the

figure on the right the user has edited this to replace the default

project1 sub-directory with gwords—a more descriptive

name for this application. Note that the Project Name,

Program Name and Project File have automatically

changed to reflect the change in the Project Directory. We

will leave these defaults as they are since they represent good

choices. See Section 35.4.4 for details.

The remaining options we won’t change either. Again they are generally

good choices. Note in particular though that we have the option turned on. You can take a look at the other

two option tabs, C Options and LibGlade Options, to

get an idea of what else you can configure (see the Reference sections

later for details). When satisfied simply click the OK

button. The main glade window’s title will have changed to be

*Gwords*,' the name of our application, replacing the previous\(<\)untitled\(>\).’

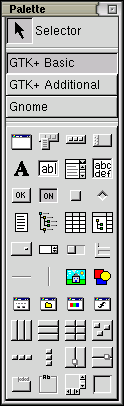

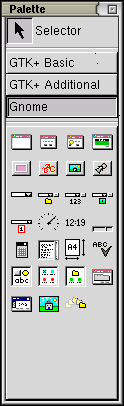

35.3.1.3 The GNOME Application Window

Now we are ready to start building our GNOME interface. We first need to create our main GNOME Application Window which will be the window displayed when our application starts up. Select the GNOME button of the Palette window to display in the palette the GNOME widgets (which are extensions to the GTK Basic widgets which are displayed by default). Identify the GNOME Application Window widget by hovering the mouse over the various widgets to display their tool tips. It is the top left widget in the palette. Simply click on it with the left mouse button to create one.

There are many other widgets available on this GNOME palette. They

include dialog boxes, message boxes, a standard GNOME About Dialog, file entry field with a browse button, a pixmap entry field

with built-in preview, and a druid. We’ll see some of these later and

%

all of them in the reference sections. For now we simply create the

GNOME Application Window.

%

all of them in the reference sections. For now we simply create the

GNOME Application Window.

You will be presented with a new window that has many of the characteristics of a GNOME application window. There is the menu bar along the top with the usual File, Edit, View, Settings, and Help menus, most including standard menu items within them. This is followed by the default toolbar with the New, Open, and Save buttons. Below this is the canvas area where you will construct your interface. At the bottom is the status bar and a progress monitor. Note that not all menus and toolbar buttons will be useful for your application and you will have others in mind that you may wish to add. Feel free to click around the window and see the menus by clicking the menu twice—once to select the menu itself then once to open up the menu to show its sub-items. Also note how widgets are identified in the Properties window as you select the widgets.

35.3.1.4 Adding Widgets

For now let’s ignore the excess of decoration. Instead we will build the basic interface components. There’s not much that we need in the interface. Certainly we need to identify the file to be word counted. Also we want to identify whether to just count the words or also the lines and bytes.

We go back to the GTK Basic palette for one of the layout

widgets. These are towards the bottom of the palette—third row from

the bottom in fact. Hover the mouse over each of them to find the

Horizontal Box, Vertical Box, Table, and

Fixed Positions. Click on the Vertical Box layout.

Now on the central canvas area of your Gwords interface

click the left mouse button. You will be asked for the number of rows

for your box—the default of 3 will do for now so just click on the

OK button. Your canvas will be divided into 3 rows. Each one

of the 3 rows can now be constructed independently—each can contain

a different widget, including further layout widgets.

%

%

We will use the first row to identify the name of the file whose contents we will be counting. We will use a file entry box to allow for the entry of the filename. We will also add a label so that we know what the file entry box is for. That means two widgets and all we have is a single row—so we need to add a Horizontal Box with two columns. Find the Horizontal Box on the GTK Basic palette, click it with the left mouse button and then click in the top row of the three rows of our canvas. When prompted select just 2 (rather than the default 3) columns for this Horizontal Box.

Labels should probably go to the left of the entry box so we will

place the label first. Select the Label widget from the

GTK Basic palette—the first item on the second row.

%

Now click in the top left box of our canvas (this is the left most of

the two cells we have just created). A GtkLabel widget should

now appear with the label

%

Now click in the top left box of our canvas (this is the left most of

the two cells we have just created). A GtkLabel widget should

now appear with the label label1 (and some resizing of the

cell might occur). This is now our first real'' widget. Of course we don't want the label to read `label1` (even though we might leave its name---as distinct from its label text---as `label1` for now). We can change the label text through the *Properties* window where you will find the fields relevant to this widget (assuming it is still the selected widget). Change the *Label* field to beFile:' (replacinglabel1`). For good measure set the X Pad field to be

10 (so that the widgets won’t look so cramped). You will see the

effect of these immediately.

% %

%

To summarise so far. A basic GNOME Application Window has

been created with the default menu bar and toolbar and a at the bottom. We have added a 3 row

Vertical Box and in the top row of this a 2 column

Horizontal Box. In the resulting top left cell we have added

a Label widget and changed the text to be

`File:.’ It also has its X Padding set to 10 to give a

less cramped layout.

35.3.1.5 Removing Widgets

You can remove widgets easily through the menu on the right mouse

button. First click on a widget with the left mouse button to select

it. The right mouse button will then list the actions you can perform

on this widget, including cut and delete. Note also the list of

`parent'' widgets all the way up to the root widget which is calledapp1`. Before proceeding let’s explore this widget pathway in

a little more detail.

35.3.1.6 The Widget Tree

All widgets in an interface are organised into a tree viewable

directly through the View\(\rightarrow\){Show

Widget Tree} menu of the main window. When a widget on your

canvas is selected the right mouse button menu allows you to view the

path up the tree from this selected widget to the root widget. The

path from the filename label (label1) above consists of

hbox1, vbox1, dock1, and finally

app1. Each of these have submenus from which you can choose

to perform actions on those widgets. For example, if you delete

vbox1 then that widget and all of its children will be

deleted from the canvas—so be careful!

We can see the Widget Tree window expanded above. Thus,

app1 contains dock1 which is made up of three

sub-components: dockitem1 contains the menu bar;

dockitem2 contains the toolbar; and vbox1 is the

Vertical Box that we added above. The Widget Tree window provides an alternative mechanism for selecting

widgets.

35.3.1.7 GNOME File Entry

Now we add the widget for entering the filename. The one we will use

is the one provided by the GNOME palette.

We

could use the text entry field of the GTK Basic palette and

add a Browse button ourselves, but the GNOME palette

GNOME File Entry widget does it all for us, and more. Click

on this widget in the palette then click in the top right cell of your

canvas. The browse button might look a bit strange (stretched out) but

don’t worry, it will sort itself out!

We

could use the text entry field of the GTK Basic palette and

add a Browse button ourselves, but the GNOME palette

GNOME File Entry widget does it all for us, and more. Click

on this widget in the palette then click in the top right cell of your

canvas. The browse button might look a bit strange (stretched out) but

don’t worry, it will sort itself out!

You can save the work you’ve done so far by clicking on the

Save button of the main glade window (not the

Save button of the window you’re working on though!). Then,

for fun, open the project again—load

/home/guest/Projects/gwords/gwords.glade. Then, on the main

glade window double click the app1 widget. You may like to

change the Border Width property of fileentry1 to

be 10 (using the Properties window after selecting the

file entry widget in the canvas). This makes it appear less cluttered.

35.3.1.8 Tooltips

Where possible you should think about tooltips—those small popup frames that appear while you hover the mouse over some item and contain useful information about the item. Tooltips provide the basic reminders that help the user ignore the application’s written documentation. Tooltips should be just a little verbose, perhaps taking up 3 or 4 lines of text. Aim to inform with the minimum number of words.

You add tooltips to widgets by first selecting the widget. Select the

text area of your fileentry1 widget—this will select

something called combo-entry1 which is contained within the

GNOME File Entry widget. Then in the Properties

window click on the Basic tab. On that page you will see the

Tooltip text entry about halfway down. Simply type in the

required text, such as:

Now hover the mouse over the file entry field on your canvas and the tooltip should pop up.

An interesting question is whether the tooltip should be associated with the file entry field as we have done or with the label of the field, or both? The answer is left as an exercise for the reader! We prefer to associate the tooltip with just the entry field itself since that is where the mouse will be hovering while you are thinking about it. On the other-hand glade’s own interface associates the tooltips with the labels.

35.3.1.10 Removing a Row

We now realise that we didn’t really need 3 rows for vbox1.

Two are sufficient. Select the third row. You may notice that the

Properties window goes blank and from the right mouse button

menu this row of our canvas is nothing more than a

Placeholder. The right mouse button menu Delete will

remove it for us. You could put it back anytime (or indeed place any

row within vbox1) through the right mouse button menu.

Select any widget within vbox1 (e.g., the Words

check button checkbutton1) and then with the right mouse

button traverse the menu to select vbox1\(\rightarrow\){Insert After}.

35.3.1.15 Display Results

After the words, lines, and bytes have been counted we will write the results to the Status Message area of the at the bottom of the window.

35.3.1.16 Running Your Interface

You can now run your interface, even though you have yet to write the code to perform the counting. Each of the following walkthroughs begins with the minimum required to run the interface without any actions behind it. You’ll want to give this a try just to make sure you can!

35.3.2 Building the C Code

Once you have your basic user interface constructed tell glade to save the project (using the Save button—this updates the file that contains the XML description of the interface) and then to build the project (using the Build button).

Start up a terminal window, such as the gnome-terminal, and

change to the project directory. There you should see an executable

file called autogen.sh. This shell script takes care of

the initial configuration of your package, running automake

to automatically generate the appropriate support files for the

configuration. It also runs the appropriate automake

components leaving you with a collection of Makefiles.

$ cd Projects/gword

$ ./autogen.sh

**Warning**: I am going to run `configure' with no arguments.

If you wish to pass any to it, please specify them on the

`./autogen.sh' command line.

processing .

deletefiles is

Creating ./aclocal.m4 ...

Running gettextize... Ignore non-fatal messages.

You should update your own `aclocal.m4' by adding the necessary

macro packages gettext.m4, lcmessage.m4 and progtest.m4 from

the directory `/aclocal'

Making ./aclocal.m4 writable ...

Running aclocal -I macros ...

Running autoheader...

...

creating Makefile

creating macros/Makefile

creating src/Makefile

creating intl/Makefile

creating po/Makefile.in

creating config.h

Now type `make' to compile the package. You can now simply run the make command to perform the

compilation (making use of the generated Makefiles). Once

completed, run the command src/gword to start up your

application.

And that’s all there is to it.

35.3.2.1 The GNU Package Management Tools

The first time you build the project all of the necessary files and sub-directories are created. From then on each time you build only the relevant files that need to be changed as a result of changes in the interface are modified.

glade generates all the necessary files to be GNU compliant and to

essentially run your application immediately (although without any

callbacks the application won’t do much). The primary location for

your C source code is in a subdirectory called src. In there

you will see 3 header files (support.h,

interface.h, and callbacks.h) and 4 source

files (support.c, interface.c,

callbacks.c, and main.c). Of these you

should never edit support.h, support.c,

interface.h, and interface.c. The first

pair contain code that glade supplies to support your application

and the latter two are the actual interface code. glade manages

these files. You will be making changes primarily in

callbacks.c to add the code for each callback. glade will

add new callbacks to the bottom of callbacks.h and

callbacks.c.

Now that you have built your interface (perhaps without any callback code just yet) you are in a position to configure, compile and run your application. The GNU automake and autoconf packages are used to simplify the management of the configuration, compilation, and installation of your application. These packages are a great help in the task of managing software projects.

Discuss the files generated by the build and how they conform to the GNU Standards.

35.3.4 Using Libglade with Python

Using libglade with python is an excellent option for rapid

prototyping and even build full strength applications. Like the use of

libglade in C there is never any need for you to convert the

.glade file (containing the XML description of the interface)

into Python code. Instead, libglade reads the XML and directly

builds the interface using the libglade library (written in C but

with an interface for Python).

The basic code is:

#! /usr/bin/env python

import gtk

import libglade

import gnome.ui

def init_app ():

"Initialise the application."

global wTree

wTree = libglade.GladeXML ("gwords.glade", "app1")

dic = {"on_quit_button_clicked" : gtk.mainquit,

"on_exit1_activate" : gtk.mainquit}

wTree.signal_autoconnect (dic)

def main ():

init_app ()

gtk.mainloop ()

if __name__ == '__main__': main ()Here we have linked the interface callback

on_exit1_activate to the library callback

gtk.mainquit. The on_exit1_activate is

associated through glade with the Exit menu item and is supplied by

default by the GNOME Application Window.

Save this code into a file called gwords.py in your

/home/guest/Projects/gwords directory. Make the file executable

with chmod u+x gwords.py. Then run the program with

./gwords.py. Your interface should come to life.

Problems arise if you don’t have the appropriate packages installed. At a minimum make sure you have python-gnome installed (this package will depend on various other python and gnome packages which should be automatically installed by choosing to install python-gnome if you are using Debian).

You may also need to ensure that the PYTHONPATH

environment variable includes the GNOME and GTK modules, but check

this only if you have problems running your Python program.

Your donation will support ongoing availability and give you access to the PDF version of this book. Desktop Survival Guides include Data Science, GNU/Linux, and MLHub. Books available on Amazon include Data Mining with Rattle and Essentials of Data Science. Popular open source software includes rattle, wajig, and mlhub. Hosted by Togaware, a pioneer of free and open source software since 1984. Copyright © 1995-2022 Graham.Williams@togaware.com Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0